Everyone knows about the Boston Housing Dataset. But I bet you might not have heard of the Ames, Iowa Housing dataset. It was featured as part of a Kaggle competition 2 years back and was significant in how it tested advanced regression techniques in the form of creative feature engineering and feature selection.

In this 3 part series, I will be going through my approach to exploring the data in the first post, followed by linear regression modeling in order to predict housing prices based on features that are non-renovatable in the second. The 3rd and final part will bring in the renovatable features to identify what features offer the best value in improving the final selling price of the house.

Imports and Overview

We first perform the usual imports

import numpy as np

import scipy.stats as stats

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

sns.set_style('whitegrid')

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

%matplotlib inline

Next we load the data

house = pd.read_csv('./housing.csv')

You will want to refer to the data dictionary file to follow along with the description of the different features in our dataset.

house.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 1460 entries, 0 to 1459

Data columns (total 81 columns):

Id 1460 non-null int64

MSSubClass 1460 non-null int64

MSZoning 1460 non-null object

LotFrontage 1201 non-null float64

LotArea 1460 non-null int64

Street 1460 non-null object

Alley 91 non-null object

LotShape 1460 non-null object

LandContour 1460 non-null object

Utilities 1460 non-null object

LotConfig 1460 non-null object

LandSlope 1460 non-null object

Neighborhood 1460 non-null object

Condition1 1460 non-null object

Condition2 1460 non-null object

BldgType 1460 non-null object

HouseStyle 1460 non-null object

OverallQual 1460 non-null int64

OverallCond 1460 non-null int64

YearBuilt 1460 non-null int64

YearRemodAdd 1460 non-null int64

RoofStyle 1460 non-null object

RoofMatl 1460 non-null object

Exterior1st 1460 non-null object

Exterior2nd 1460 non-null object

MasVnrType 1452 non-null object

MasVnrArea 1452 non-null float64

ExterQual 1460 non-null object

ExterCond 1460 non-null object

Foundation 1460 non-null object

BsmtQual 1423 non-null object

BsmtCond 1423 non-null object

BsmtExposure 1422 non-null object

BsmtFinType1 1423 non-null object

BsmtFinSF1 1460 non-null int64

BsmtFinType2 1422 non-null object

BsmtFinSF2 1460 non-null int64

BsmtUnfSF 1460 non-null int64

TotalBsmtSF 1460 non-null int64

Heating 1460 non-null object

HeatingQC 1460 non-null object

CentralAir 1460 non-null object

Electrical 1459 non-null object

1stFlrSF 1460 non-null int64

2ndFlrSF 1460 non-null int64

LowQualFinSF 1460 non-null int64

GrLivArea 1460 non-null int64

BsmtFullBath 1460 non-null int64

BsmtHalfBath 1460 non-null int64

FullBath 1460 non-null int64

HalfBath 1460 non-null int64

BedroomAbvGr 1460 non-null int64

KitchenAbvGr 1460 non-null int64

KitchenQual 1460 non-null object

TotRmsAbvGrd 1460 non-null int64

Functional 1460 non-null object

Fireplaces 1460 non-null int64

FireplaceQu 770 non-null object

GarageType 1379 non-null object

GarageYrBlt 1379 non-null float64

GarageFinish 1379 non-null object

GarageCars 1460 non-null int64

GarageArea 1460 non-null int64

GarageQual 1379 non-null object

GarageCond 1379 non-null object

PavedDrive 1460 non-null object

WoodDeckSF 1460 non-null int64

OpenPorchSF 1460 non-null int64

EnclosedPorch 1460 non-null int64

3SsnPorch 1460 non-null int64

ScreenPorch 1460 non-null int64

PoolArea 1460 non-null int64

PoolQC 7 non-null object

Fence 281 non-null object

MiscFeature 54 non-null object

MiscVal 1460 non-null int64

MoSold 1460 non-null int64

YrSold 1460 non-null int64

SaleType 1460 non-null object

SaleCondition 1460 non-null object

SalePrice 1460 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(3), int64(35), object(43)

memory usage: 924.0+ KB

Looking at our dataset, we observe that there are altogether 1460 houses with 81 features which are categorized to 3 floats, 35 integers and 43 string (possibly categorical) datatypes. Some features have null values which range from as little as 1 (Electrical) to as many as 1453 (PoolQC)

Since we will be predicting on the saleprice, let us first analyze our dependent variable.

Analysis of dependent variable

house['SalePrice'].describe()

count 1460.000000

mean 180921.195890

std 79442.502883

min 34900.000000

25% 129975.000000

50% 163000.000000

75% 214000.000000

max 755000.000000

Name: SalePrice, dtype: float64

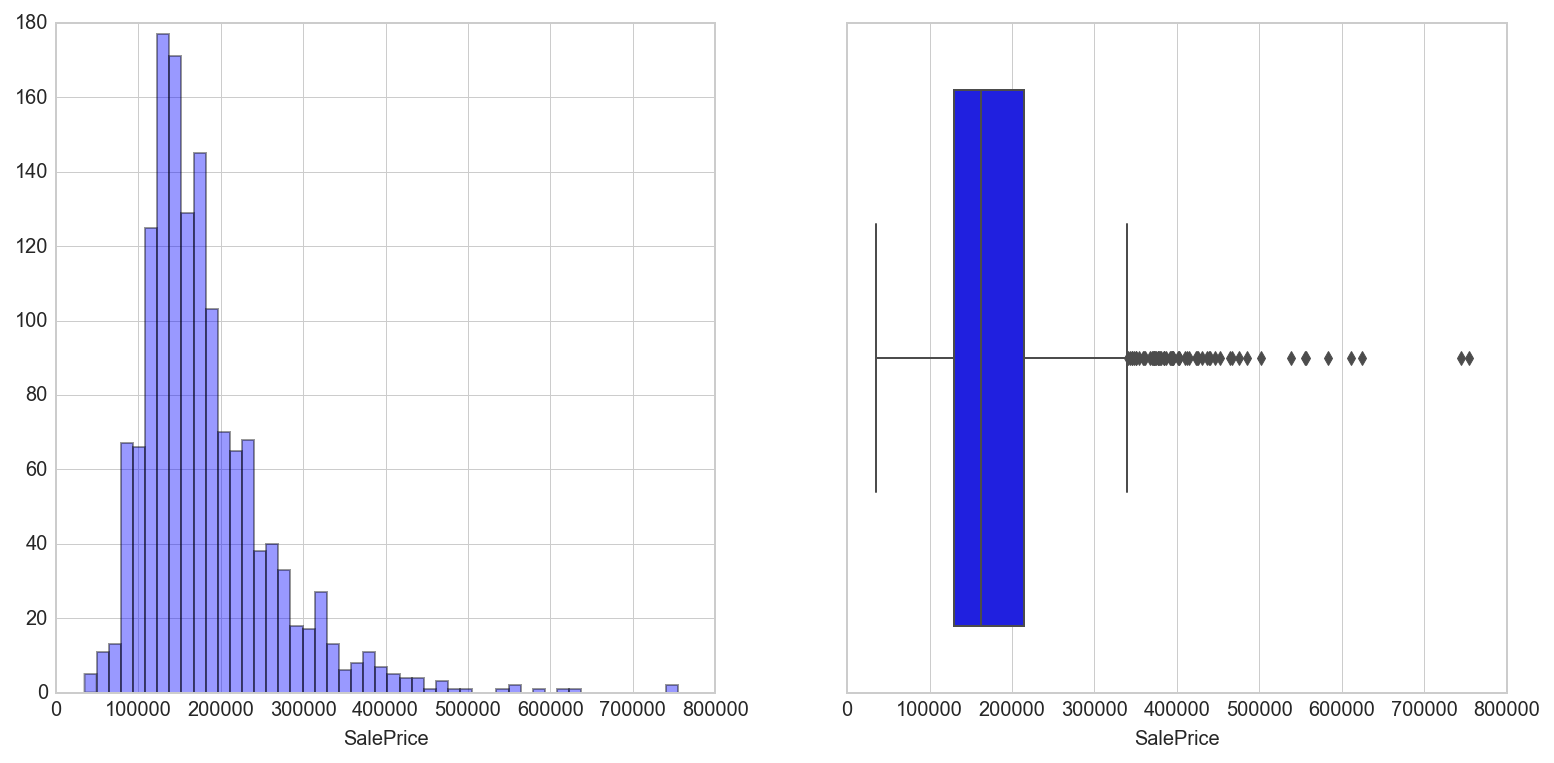

We can see that the median selling price of houses in our dataset is $163,000. The mean is $180,921 however, suggesting a positively skewed distribution. Let’s take a look at the distribution of the saleprice

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,2, figsize=(13,6))

sns.distplot(house['SalePrice'], kde=False, ax=ax[0])

sns.boxplot(house['SalePrice'], ax=ax[1])

plt.show()

The dependent variable looks to be right skewed due to several high valued houses. The boxplot shows the presence of outliers beyond $340,000. For the purpose of linear regression, we do not have to assume that our dependent variable follows a normal distribution. We will however keep in mind the fact that we might want to do some outlier processing to improve regression results.

Initial cleaning of data

Before we dive deeper into the features, we will perform some preprocessing work. They include:

- Cleaning the column headers and index

- Checking for duplicates

- Checking for negative numbers

- Removing non-residential houses

- Handling the null values

1. Cleaning column headers and index

Column headers look fine except that I prefer to work with small caps. Let’s define a function to transform them.

def clean_columns(df):

df.columns = [x.lower() for x in df.columns]

return df

clean_columns(house)

The id column is unique to each house and can be set as the index.

house.set_index('id', inplace=True )

2. Check for duplicates

We now look for any repeat observations in our data

house.duplicated().sum()

0

Looks like there aren’t any

3. Check for negative numbers

Taking a look at the data dictionary, there doesn’t seem to be any reason for negative numbers. Let’s check if there are any in our dataset

house.lt(0).sum().sum()

0

Just as expected.

4. Remove non-residential houses

Looking at the mszoning feature, there seems to be some buildings in our dataset that could belong to non-residential types including commercial and industrial types. Let’s take a look at the distribution of housing types in our dataset.

house['mszoning'].value_counts()

RL 1151

RM 218

FV 65

RH 16

C (all) 10

Name: mszoning, dtype: int64

It seems that other than 10 commercial buildings, the other types are residential. We will remove these 10 commercial buildings to narrow our model predictive ability to only residential building types.

house = house.loc[house['mszoning'] != 'C (all)',:]

house.shape

(1450, 80)

#Reset index and drop id column

house.reset_index(drop=True, inplace=True)

house.drop('id', axis=1, inplace=True)

5. Handle Null values

As a rule of thumb, features with more than 70% null values should be dropped as imputing them with artificial values will not be a good representation of the actual observations.

In this case, we will drop features that have more than 1020 null values

house.isnull().sum().sort_values(ascending=False)

poolqc 1443

miscfeature 1398

alley 1361

fence 1172

fireplacequ 681

lotfrontage 259

garagetype 79

garagecond 79

garagefinish 79

garagequal 79

garageyrblt 79

bsmtfintype2 38

bsmtexposure 38

bsmtqual 37

bsmtcond 37

bsmtfintype1 37

masvnrarea 8

masvnrtype 8

electrical 1

--- Truncated ---

There are 4 features that do not fulfill our criteria of less than 70% NaNs. I decided to drop those 4 as they will not be useful as predictors. A further check also showed that poolarea is highly correlated to poolqc and only has values for the same 7 houses, the rest are 0. We will drop that feature too.

house.drop(['poolqc', 'miscfeature', 'alley', 'fence', 'poolarea'], axis=1, inplace=True)

house.shape

(1450, 75)

Let’s go down the list of the other features to determine how we will impute the NaN values.

house['fireplacequ'].unique()

array([nan, 'TA', 'Gd', 'Fa', 'Ex', 'Po'], dtype=object)

The nan values in fireplacequ indicates that a house does not have a fireplace. We will impute those with ‘NA’

house['fireplacequ'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

The lot frontage is next in line

house['lotfrontage'].describe()

count 1191.000000

mean 70.052897

std 24.301013

min 21.000000

25% 59.000000

50% 70.000000

75% 80.000000

max 313.000000

Name: lotfrontage, dtype: float64

Seeing as to how the feature looks to be normally distributed (mean and median are very similar), we will impute with the median value.

house['lotfrontage'].fillna(house['lotfrontage'].median(), inplace = True)

Now we look at the null values in the garage

house['garagecond'].unique()

array(['TA', nan, 'Gd', 'Fa', 'Po', 'Ex'], dtype=object)

house['garagetype'].unique()

array(['Attchd', 'Detchd', 'BuiltIn', 'CarPort', nan, 'Basment', '2Types'], dtype=object)

house['garagefinish'].unique()

array(['RFn', 'Unf', 'Fin', nan], dtype=object)

house['garagequal'].unique()

array(['TA', 'Fa', 'Gd', nan, 'Ex', 'Po'], dtype=object)

house['garageyrblt'].unique()

array([ 2003., 1976., 2001., 1998., 2000., 1993., 2004., 1973.,

1931., 1939., 1965., 2005., 1962., 2006., 1960., 1991.,

1970., 1967., 1958., 1930., 2002., 1968., 2007., 2008.,

1957., 1920., 1966., 1959., 1995., 1954., 1953., nan,

1983., 1977., 1997., 1985., 1963., 1981., 1964., 1999.,

1935., 1990., 1945., 1987., 1989., 1915., 1956., 1948.,

1974., 2009., 1950., 1961., 1921., 1979., 1951., 1969.,

1936., 1975., 1971., 1923., 1984., 1926., 1955., 1986.,

1988., 1916., 1932., 1972., 1918., 1980., 1924., 1996.,

1940., 1949., 1994., 1910., 1978., 1982., 1992., 1925.,

1941., 2010., 1927., 1947., 1937., 1942., 1938., 1952.,

1928., 1922., 1934., 1906., 1914., 1946., 1908., 1929.,

1933.])

Similar to the fireplace, we will impute ‘NA’ for houses without garage. The only exception is the garageyrblt where we will impute with the median year.

house['garagecond'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['garagetype'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['garageyrblt'].fillna(house['garageyrblt'].median(), inplace=True)

house['garagefinish'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['garagequal'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

Next we look at the null values in the basement

house['bsmtexposure'].unique()

array(['No', 'Gd', 'Mn', 'Av', nan], dtype=object)

house['bsmtfintype2'].unique()

array(['Unf', 'BLQ', nan, 'ALQ', 'Rec', 'LwQ', 'GLQ'], dtype=object)

house['bsmtfintype1'].unique()

array(['GLQ', 'ALQ', 'Unf', 'Rec', 'BLQ', nan, 'LwQ'], dtype=object)

house['bsmtcond'].unique()

array(['TA', 'Gd', nan, 'Fa', 'Po'], dtype=object)

house['bsmtqual'].unique()

array(['Gd', 'TA', 'Ex', nan, 'Fa'], dtype=object)

The values are all ordinal in nature. We will impute ‘NA’ to all of them.

house['bsmtexposure'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['bsmtfintype2'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['bsmtfintype1'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['bsmtcond'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

house['bsmtqual'].fillna('NA', inplace=True)

Next up is the masonry veneer area and type

house['masvnrtype'].unique()

array(['BrkFace', 'None', 'Stone', 'BrkCmn', nan], dtype=object)

house['masvnrarea'].unique()

array([ 1.96000000e+02, 0.00000000e+00, 1.62000000e+02,

3.50000000e+02, 1.86000000e+02, 2.40000000e+02,

2.86000000e+02, 3.06000000e+02, 2.12000000e+02,

1.80000000e+02, 3.80000000e+02, 2.81000000e+02,

6.40000000e+02, 2.00000000e+02, 2.46000000e+02,

1.32000000e+02, 6.50000000e+02, 1.01000000e+02,

4.12000000e+02, 2.72000000e+02, 4.56000000e+02,

1.03100000e+03, 1.78000000e+02, 5.73000000e+02,

3.44000000e+02, 2.87000000e+02, 1.67000000e+02,

1.11500000e+03, 4.00000000e+01, 1.04000000e+02,

5.76000000e+02, 4.43000000e+02, 4.68000000e+02,

6.60000000e+01, 2.20000000e+01, 2.84000000e+02,

---Truncated---

Seeing as to how there is already a ‘None’ value in masvnrtype and a 0 value in masvnrarea, we will impute all missing values in masvnrtype to ‘None and that in masvnrarea to 0.

house['masvnrarea'].fillna(0, inplace=True)

house['masvnrtype'].fillna('None', inplace=True)

The final feature to consider for Null handling is the electrical column

house['electrical'].unique()

array(['SBrkr', 'FuseF', 'FuseA', 'FuseP', 'Mix', nan], dtype=object)

They are all unique values. We will impute with the mode for that single house that doesn’t have a value.

house['electrical'].fillna(house['electrical'].mode(), inplace=True)

house.isnull().sum().sum()

0

Great, now that all null values have been handled, we will look into feature engineering.

Feature Engineering

Now, let’s see if we can create some new features that can help us better explain the data.

We will take a look at year features, combining features that describe the same thing, area features, bathroom features, ordinal features, features rating the quality and condition and finally cyclical features.

Year features

Let’s first explore the features with year values. The age of the house, garage and its furnishings might be better able to explain the prices it was sold at. We will derive these values from the year they were commenced right up to when they were sold.

house['houseage'] = house['yrsold'] - house['yearbuilt']

house['garageage'] = house['yrsold'] - house['garageyrblt']

house['furnishage'] = house['yrsold'] - house['yearremodadd']

house.drop(['yearbuilt', 'garageyrblt', 'yearremodadd'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Combining features describing the same thing

Next we combine both condition1 and condition2 into one feature as they are referring to the same set of values.

house['condition'] = np.where(house['condition1'] == house['condition2'], house['condition1'], house['condition1'] + house['condition2'])

house.drop(['condition1', 'condition2'], axis=1, inplace=True)

We do the same for Exterior1st and Exterior 2nd

house['exterior'] = np.where(house['exterior1st'] == house['exterior2nd'], house['exterior1st'], house['exterior1st'] + house['exterior2nd'])

house.drop(['exterior1st', 'exterior2nd'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Area features

Next we look at the square feet measurements and see if we can engineer or remove some features

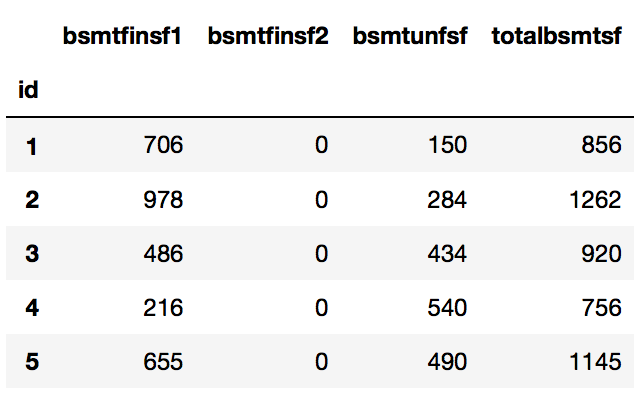

house[['bsmtfinsf1', 'bsmtfinsf2', 'bsmtunfsf', 'totalbsmtsf']].head()

It looks like totalbsmtsf is a sum total of the other 3 columns. And it seems that bsmtinsf2 is very sparse. We will drop totalbsmtsf and combine bsmtfinsf1 and bsmtfinsf2 into a new feature.

house['bsmtfinsf'] = house['bsmtfinsf1'] + house['bsmtfinsf2']

house.drop(['bsmtfinsf1', 'bsmtfinsf2', 'totalbsmtsf'], axis=1, inplace = True)

Next we look at the square feet coverage of the house.

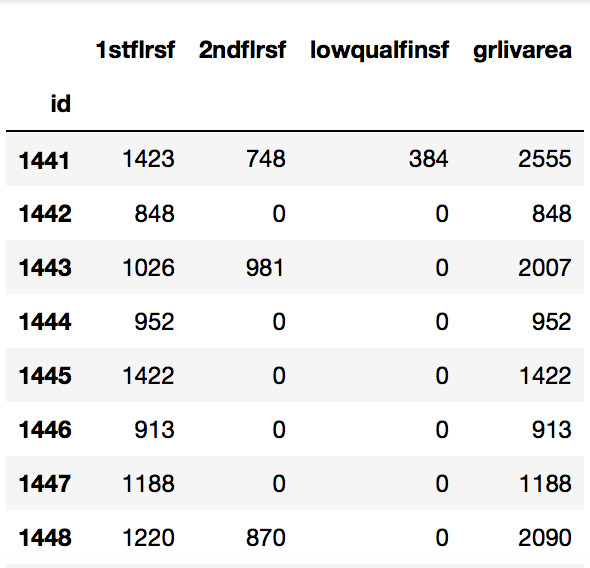

house[['1stflrsf', '2ndflrsf', 'lowqualfinsf', 'grlivarea']].tail(20)

Truncated to show sum of 3 columns equals to grlivarea

Truncated to show sum of 3 columns equals to grlivarea

It seems that grlivarea is comprised of the sum of the other 3 columns. Both 2ndflrsf and lowqualfinsf look considrably sparse. Let’s investigate.

house['2ndflrsf'].value_counts()

0 824

728 10

504 9

672 8

546 8

720 7

600 7

---Truncated---

house['lowqualfinsf'].value_counts()

0 1425

80 3

360 2

371 1

53 1

120 1

---Truncated---

Since both features are considerably sparse, I will drop them as well as the 1stflrsf column as they are all included in grlivarea and will be collinear.

house.drop(['1stflrsf', '2ndflrsf', 'lowqualfinsf'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Final area to look at is the porch

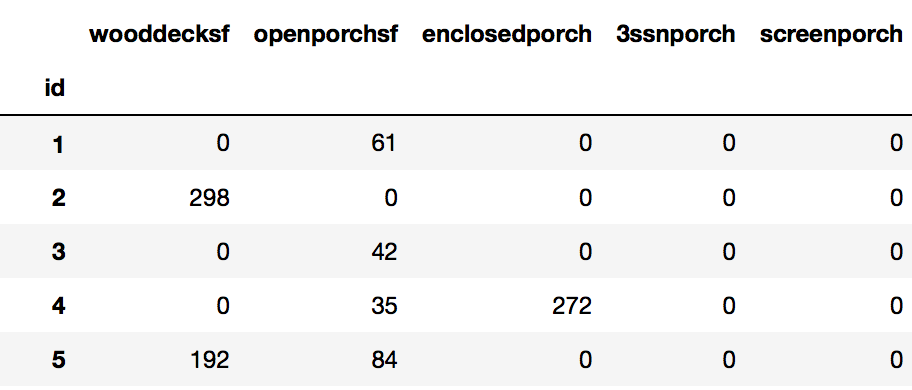

house[['wooddecksf', 'openporchsf', 'enclosedporch', '3ssnporch', 'screenporch']]

Upon performing value_counts(), all 5 features have considerable amount of 0 values. I will create a new porch feature to combine all of this data.

house['porch'] = house['wooddecksf'] + house['openporchsf'] + house['enclosedporch'] + house['3ssnporch'] + house['screenporch']

house.drop(['wooddecksf', 'openporchsf', 'enclosedporch', '3ssnporch', 'screenporch'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Bathroom features

Let’s now take a look at the bathroom features

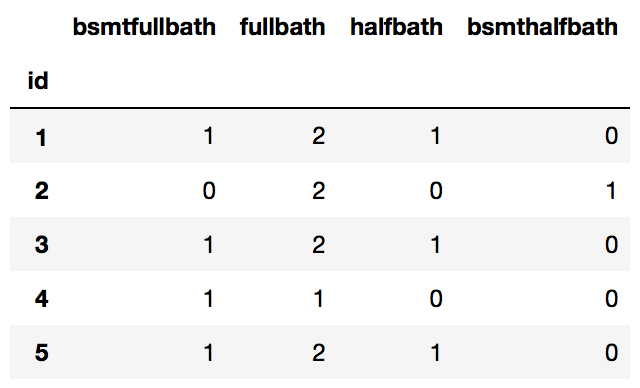

house[['bsmtfullbath', 'fullbath', 'halfbath', 'bsmthalfbath']].head(20)

Both the halfbath features look to be rather sparse. Let’s investigate.

house['halfbath'].value_counts()

0 904

1 534

2 12

Name: halfbath, dtype: int64

house['bsmthalfbath'].value_counts()

0 1369

1 79

2 2

Name: bsmthalfbath, dtype: int64

Indeed they are and might not be useful predictors for us. Let’s combine all the bathrooms values into on bath feature indicating number of bathrooms in the house.

house['bath'] = house['bsmthalfbath'] + house['bsmtfullbath'] + house['halfbath'] + house['fullbath']

house.drop(['bsmthalfbath', 'bsmtfullbath', 'halfbath', 'fullbath'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Ordinal Features

Some of the features have an order to their values. An Excellent is definitely better than a Poor rating. We will encode these ordinal features to account for their difference in weights

six_ratings = lambda x: 5 if x=='Ex' else 4 if x=='Gd' else 3 if x=='TA' else 2 if x=='Fa' else 1 if x=='Po' else 0

five_ratings = lambda x: 5 if x=='Ex' else 4 if x=='Gd' else 3 if x=='TA' else 2 if x=='Fa' else 1

seven_ratings = lambda x: 6 if x=='GLQ' else 5 if x=='ALQ' else 4 if x=='BLQ' else 3 if x=='Rec' else 2 if x=='LWQ'\

else 1 if x=='Unf' else 0

house['exterqual'] = house['exterqual'].apply(five_ratings)

house['extercond'] = house['extercond'].apply(five_ratings)

house['bsmtqual'] = house['bsmtqual'].apply(six_ratings)

house['bsmtcond'] = house['bsmtcond'].apply(six_ratings)

house['bsmtfintype'] = house['bsmtfintype1'].apply(seven_ratings) + house['bsmtfintype2'].apply(seven_ratings)

house['bsmtexposure'] = house['bsmtexposure'].apply(lambda x: 4 if x=='Gd' else 3 if x=='Av' else 2 if x=='Mn' else 1 if x=="No" else 0)

house['heatingqc'] = house['heatingqc'].apply(five_ratings)

house['kitchenqual'] = house['kitchenqual'].apply(five_ratings)

house['fireplacequ'] = house['fireplacequ'].apply(six_ratings)

house['garagequal'] = house['garagequal'].apply(six_ratings)

house['garagecond'] = house['garagecond'].apply(six_ratings)

house.drop(['bsmtfintype1', 'bsmtfintype2'], axis=1, inplace=True)

We drop bsmtfintype1 and 2 as they have been combined to form a single bsmtfintype feature.

Quality and Condition

There are several features that are rated on the quality and condition. Let’s take a look at these features to decide if we should take any action.

We first perform chi2 tests of independence to look for any correlation between these categorical variables.

from scipy.stats import chi2_contingency

observed = pd.crosstab(house['overallqual'], house['overallcond'])

chi2_contingency(observed)

1224.807874384609,

3.9260754195024299e-209

---Truncated---

The second value, the P-value, tells us that we should reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the variables. We will combine the features into one that is the sum of the values.

house['overallqualcond'] = house['overallqual'] + house['overallcond']

house.drop(['overallqual', 'overallcond'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Let’s now do the same with garage, basement and exterior

observed = pd.crosstab(house['garagequal'], house['garagecond'])

chi2_contingency(observed)

3618.5201510975894,

0.0

---Truncated---

observed = pd.crosstab(house['bsmtqual'], house['bsmtcond'])

chi2_contingency(observed)

1621.616686005882,

0.0

---Truncated---

observed = pd.crosstab(house['extercond'], house['exterqual'])

chi2_contingency(observed)

149.82854810419238,

6.1426177291591305e-26

---Truncated---

The P-values for all 3 are less than 0.05 which means we reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between the variables. Let’s combine each pair into one feature and drop the individual features from our dataset.

house['extercondqual'] = house['extercond'] + house['exterqual']

house['garagecondqual'] = house['garagecond'] + house['garagequal']

house['bsmtcondqual'] = house['bsmtcond'] + house['bsmtqual']

house.drop(['extercond', 'exterqual', 'garagecond', 'garagequal', 'bsmtcond', 'bsmtqual'], axis=1, inplace=True)

Cyclical Features

The month sold variable is cyclical in nature as december is close to january and not as far apart as 1 is from 12. Let’s map observations onto a circle and compute x- and y- components of that point using sin and cos functions

house['mosold_sin'] = np.sin((house['mosold']-1) * (2. * np.pi/12))

house['mosold_cos'] = np.cos((house['mosold']-1) * (2. * np.pi/12))

house.drop('mosold', axis=1, inplace=True)

house.shape

(1450, 57)

Through this stage of feature engineering, we have reduced our feature set to 57. We will next look at filter methods of feature selection to further reduce the number of dimensions in our dataset.

Feature Selection - Filter methods

Next we select a subset of the features that best explains the target variable, which in our case, is the saleprice. We do so by performing the following tests on our feature set

- Pearson Correlation (Check for multicollinearity)

- Variance Inflation Factor (Check for multicollinearity)

- Eliminate features with low variance

First, we extract out our numeric variables

continuous_features = house._get_numeric_data()

continuous_features.shape

(1450, 32)

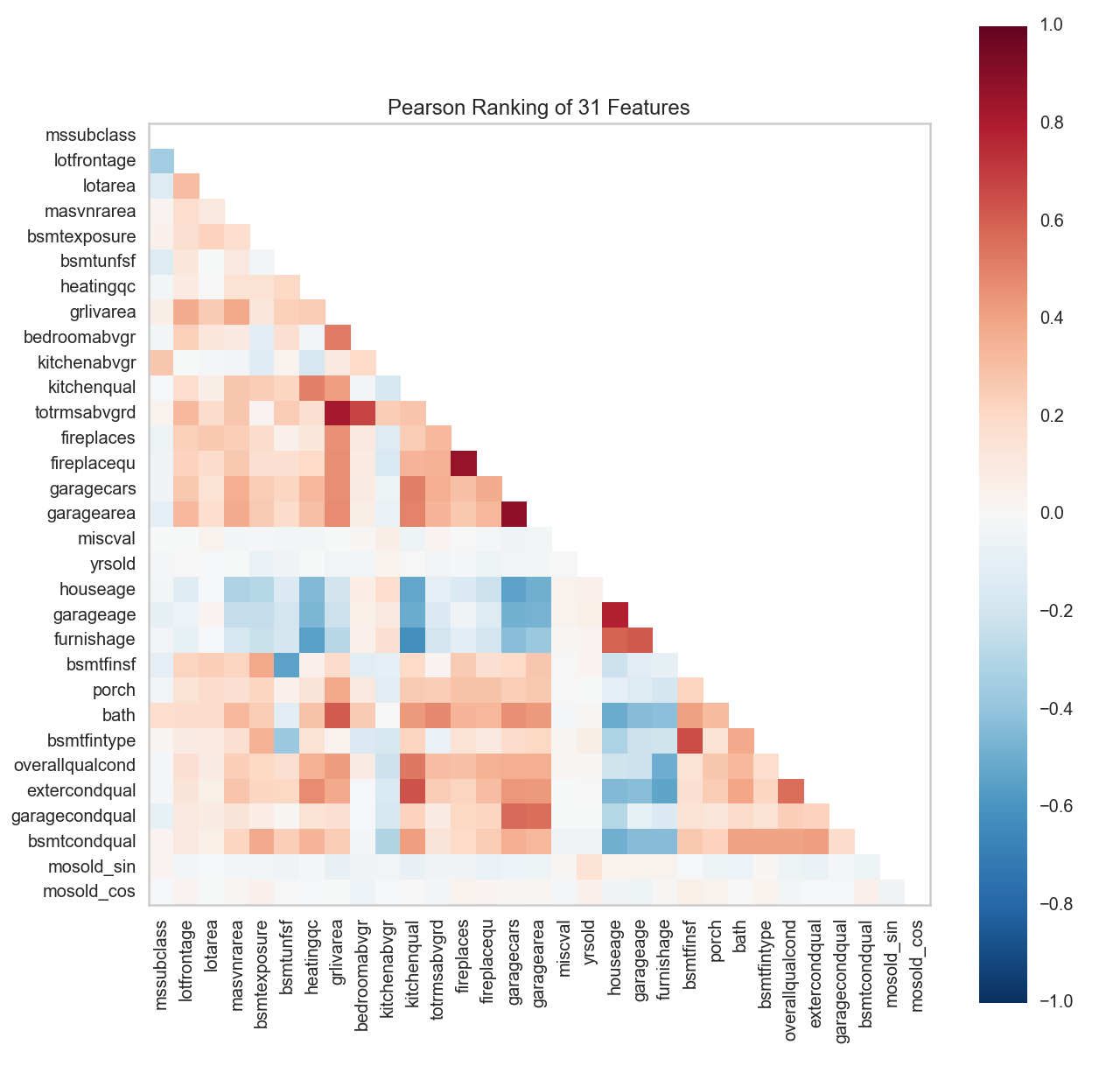

1. Pearson Correlation

We will be using the yellowbrick package for visualization.

from yellowbrick.features.rankd import Rank2D, Rank1D

y = continuous_features['saleprice']

X = continuous_features.drop(['saleprice'], axis=1)

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

visualizer = Rank2D()

visualizer.fit(X,y)

visualizer.transform(X)

visualizer.poof()

We can see firstly that garagecars and garagearea are highly correlated. We will drop garagecars as it looks to have higher correlation with other variables. Next, we can observe that fireplacequ and fireplaces are also highly correlated. We will drop fireplacequ as it too looks to have higher correlation with other variables. houseage and garageage look to be rather highly correlated too. We will drop houseage in favour of the other variable with lower correlation to other predictors. Finally, totrmsabvdrd looks to be highly correlated with grlivarea and bedroomabvgr. Let’s investigate!

house.drop(['garagecars', 'fireplacequ', 'houseage'], axis=1, inplace=True)

observed = pd.crosstab(house['totrmsabvgrd'], house['bedroomabvgr'])

chi2_contingency(observed)

2976.3876070778488,

0.0

---Truncated---

It seems reasonable enough to understand why a relationship is observed between number of bedrooms above grade and total number of rooms above grade, which is further proven by the significant chi2 test result. Let’s look at the relationship between totrmsabvgrd, a categorical variable, and the grlivarea, a continuous one using an ANOVA one-way test.

from scipy import stats

import statsmodels.api as sm

from statsmodels.formula.api import ols

mod = ols('grlivarea ~ totrmsabvgrd',

data=house).fit()

aov_table = sm.stats.anova_lm(mod, typ=2)

print aov_table

sum_sq df F PR(>F)

totrmsabvgrd 2.721091e+08 1.0 3090.157687 0.0

Residual 1.275061e+08 1448.0 NaN NaN

There is a significant relationship between both variables as evidenced by the low p-value of the ANOVA test. We’ll drop totrmsabvgrd as a potential predictor.

house.drop('totrmsabvgrd', axis=1, inplace=True)

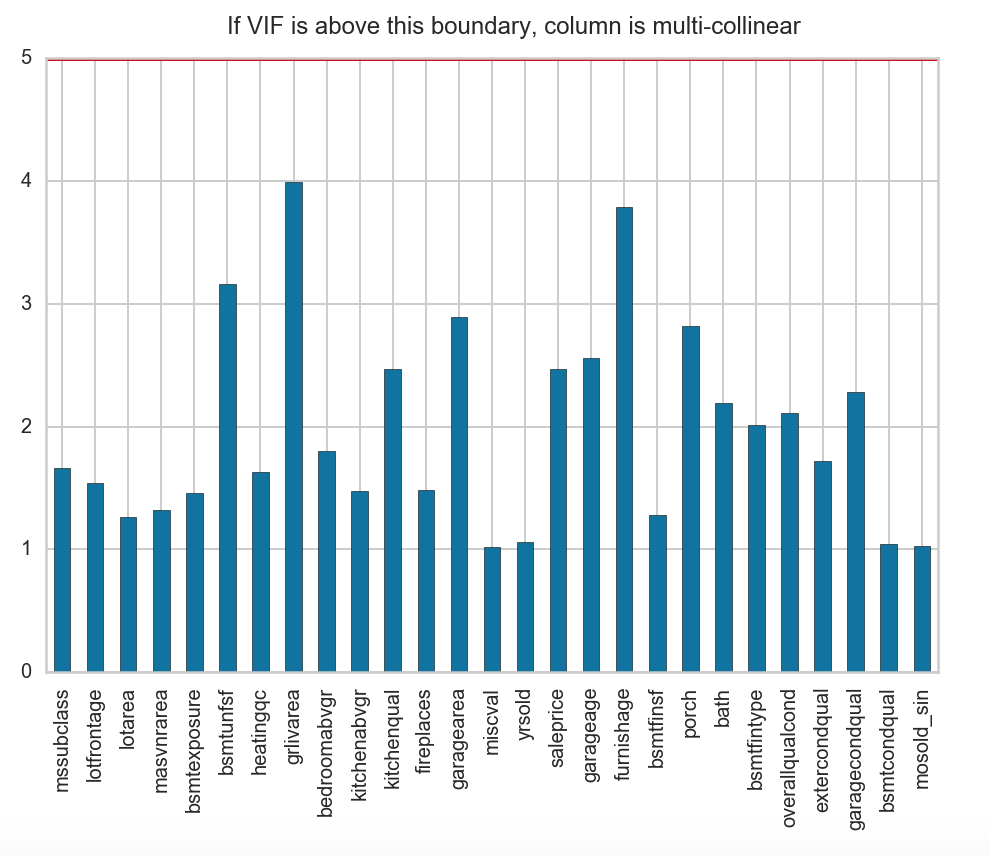

2. Variance Inflation Factor

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) checks to see if any of the features in a dataset tends to exhibit multicollinearity with other variables. This is accomplished through an analysis of how ‘inflated’ the variance of the coefficient of a feature becomes in comparison to the other features in a multiple linear regression. A VIF more than 5 indicates high correlation while values between 1-5 show moderate correlation.

#We need to reset our continuous features and X as we have dropped some variables

continuous_features = house._get_numeric_data()

X = continuous_features.drop('saleprice', axis=1)

#We need to standardize our features first

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

Xs = scaler.fit_transform(X)

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

VIF = [(continuous_features.columns[i], variance_inflation_factor(Xs, i)) for i in range(Xs.shape[1])]

VIF_df = pd.DataFrame(list(zip(*VIF)[1]), index = list(zip(*VIF)[0]))

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

VIF_df.plot(kind = 'bar', legend = False, ax = ax)

ax.axhline(5, c = 'r', lw = 3)

ax.text(5, 5.2, 'If VIF is above this boundary, column is multi-collinear')

plt.show()

It would seem that none of our other features are highly correlated with each other although several features are moderately correlated.

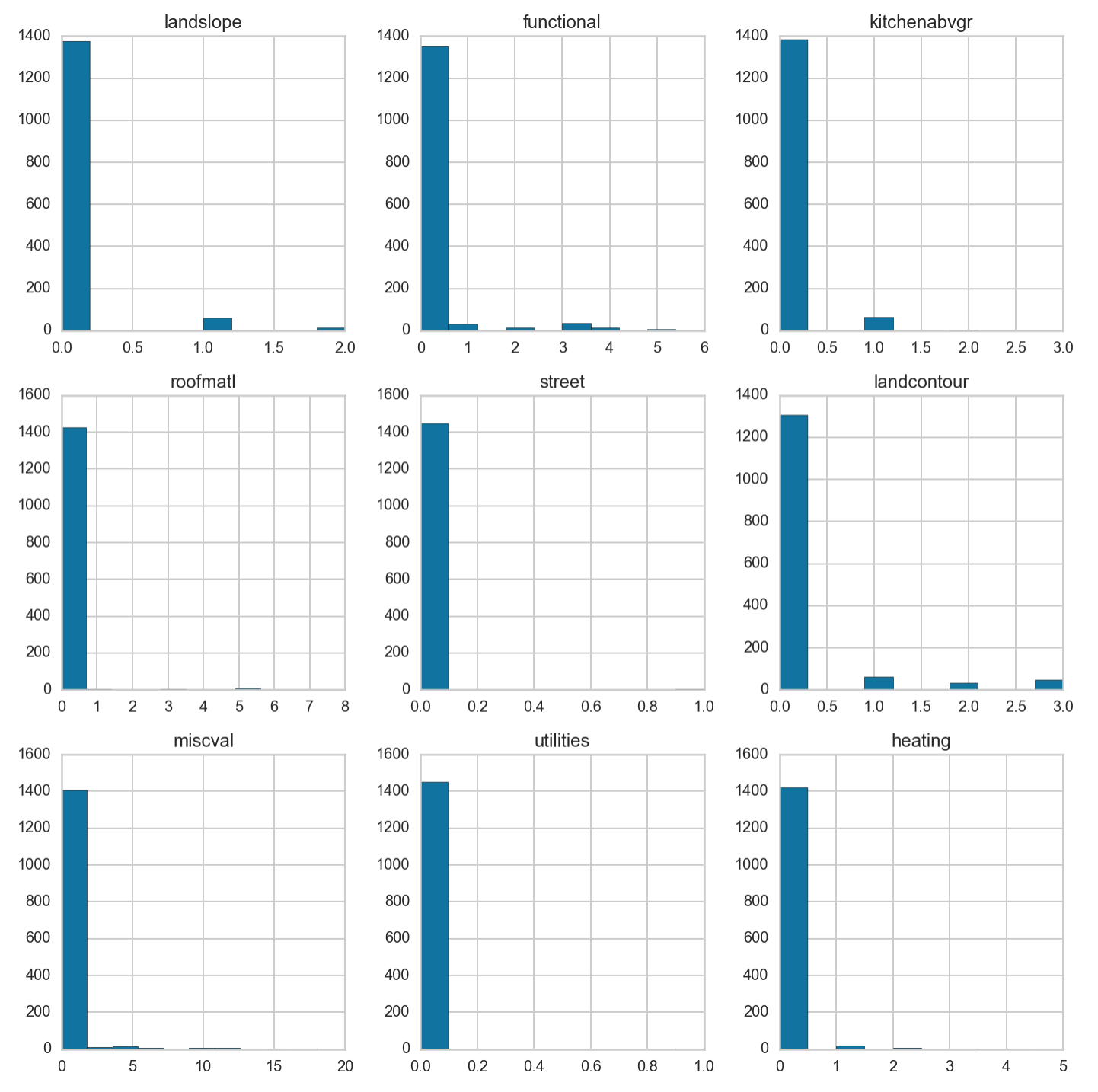

3. Low Variance Check

We next identify features with low or near zero variance through the following function. Near zero variance features are qualified as those with a 19x difference in the highest value to the next highest value including having the total number of distinct values to be less than 10% of the total number of samples.

Here’s a function that accomplishes this check

def nearZeroVariance(X, freqCut = 95 / 5, uniqueCut = 5):

'''

Determine predictors with near zero or zero variance.

Inputs:

X: pandas data frame

freqCut: the cutoff for the ratio of the most common value to the second most common value

uniqueCut: the cutoff for the percentage of distinct values out of the number of total samples

Returns a tuple containing a list of column names: (zeroVar, nzVar)

'''

colNames = X.columns.values.tolist()

freqRatio = dict()

uniquePct = dict()

for names in colNames:

counts = (

(X[names])

.value_counts()

.sort_values(ascending = False)

.values

)

if len(counts) == 1:

freqRatio[names] = -1

uniquePct[names] = (float(len(counts)) / len(X[names])) * 100

continue

freqRatio[names] = counts[0] / counts[1]

uniquePct[names] = (float(len(counts)) / len(X[names])) * 100

zeroVar = list()

nzVar = list()

for k in uniquePct.keys():

if freqRatio[k] == -1:

zeroVar.append(k)

if uniquePct[k] < uniqueCut and freqRatio[k] > freqCut:

nzVar.append(k)

return(zeroVar, nzVar)

We will put our entire feature set into the function.

X = house.drop('saleprice', axis=1)

zeroVar, nzVar = nearZeroVariance(X)

print zeroVar, nzVar

[] ['landslope', 'functional', 'kitchenabvgr', 'roofmatl', 'street', 'landcontour', 'miscval', 'utilities', 'heating']

These are the featrues that are identified to have low variance. Let’s take a look at their distribution.

features = house.loc[:, ['landslope', 'functional', 'kitchenabvgr', 'roofmatl', 'street', 'landcontour', 'miscval',

'utilities', 'heating']]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols = 3, figsize = (16,16))

for idx, col_name in enumerate(features.columns):

row = int(idx / 3)

col = int(idx % 3)

ax[row][col].set_title(col_name)

ax[row][col].hist(house[col_name].factorize()[0])

plt.tight_layout()

fig.patch.set_facecolor('white')

We can indeed observe the high prevalence for one value, the 0 value, and minimal contribution by the others. We will drop these features from our dataset.

house.drop(['landslope', 'functional', 'kitchenabvgr', 'roofmatl', 'street', 'landcontour', 'miscval', 'utilities', 'heating'], axis=1, inplace=True)

house.shape

(1450, 44)

By performing a series of feature engineering and feature selection, we have reduced our feature set from 81 variables to the 44 currently.

In part 2, we will further process the data in order to efficiently create a model that can predict housing prices based on features of property sold previously. In particular, we will identify what are the non-renovatable features of a house that can be used to predict the value of a house and what renovations can best explain the variance in price on the actual selling price of a property and its predicted value.

The repo for this series can be found here